Archive

‘Some of the sessions were very long in the

preparation of the sound and the arrangements

had at times various percussion players,

sometimes two or three, two drummers, four

or five acoustic guitars, two pianos and even

two basses on one of the tracks. The songs

were played over and over again until the

arrangements were sorted out so that the

engineer in the control room could get

the sound with Phil Spector. Many of the

tracks were virtually live.’

George

On Tuesday 26 May 1970, George Harrison entered Studio Three at EMI Studios, Abbey Road in St John’s Wood, London. To the public the studio was called Abbey Road, but for the engineers working there it was still EMI, until the name was officially changed in 1976. It had been George’s musical home since The Beatles first arrived there for an audition in June 1962. The Beatles are more associated with Studio Two, but had plenty of experience working in Studio Three. They had recorded songs for the Abbey Road album in Studio Three in 1969, including ‘Something’. George knew the room, and the engineers, very well.

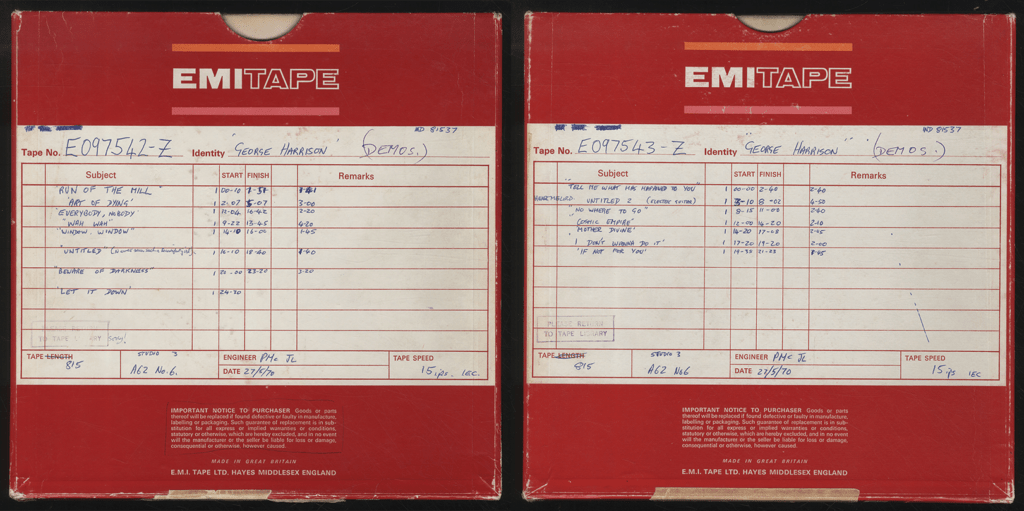

George spent the first of two days recording thirty demos of songs that were being considered for his new, as yet untitled, album. There were recent compositions plus numerous songs that had been written during the past several years, but had not found their way onto albums or singles by The Beatles. There were also two co-writes with Bob Dylan, and two unreleased compositions by Dylan that George had learned directly from him.

George recorded fifteen demos on the first day with two of his oldest friends, Ringo Starr and Klaus Voormann. They were part of the studio team that George had assembled over the past two years for the albums on Apple Records that he had produced for Jackie Lomax, The Radha Krsna Temple, Doris Troy and Billy Preston.

On the second day, George recorded fifteen additional demos for his co-producer Phil Spector.

George had recently experienced Spector’s production style first-hand while playing on John Lennon’s ‘Instant Karma’ in January and then attending Spector’s mixing of The Beatles’ Let It Be in March and April. That album had just been released earlier in the month on 8 May.

The tracking sessions with the full band started on 28 May. Spector’s legendary ‘Wall of Sound’ required a large group of musicians to create an orchestra of rock instrumentation – multiple guitars, keyboards, basses, drums and percussion. George had a team of exceptional musicians to draw upon, his counterpart to Spector’s ‘Wrecking Crew’ in LA.

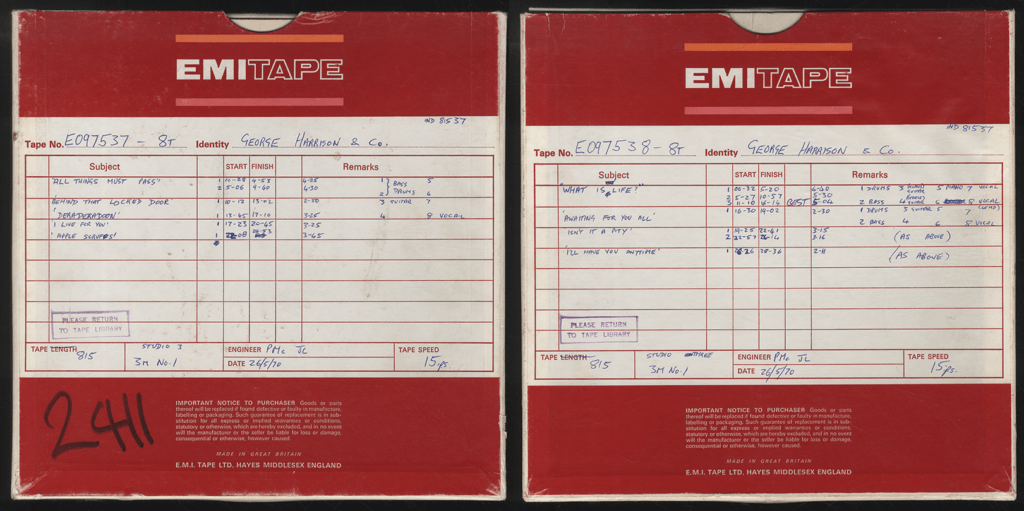

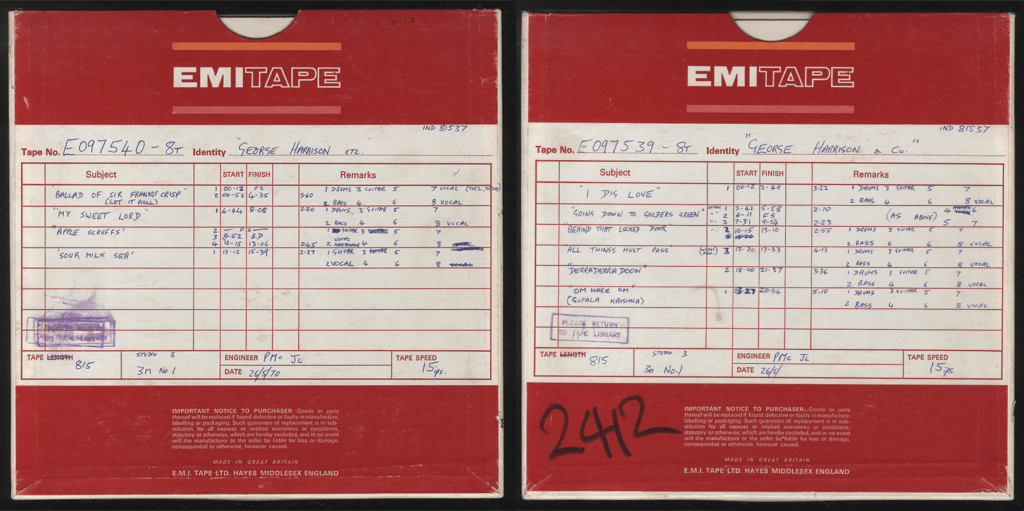

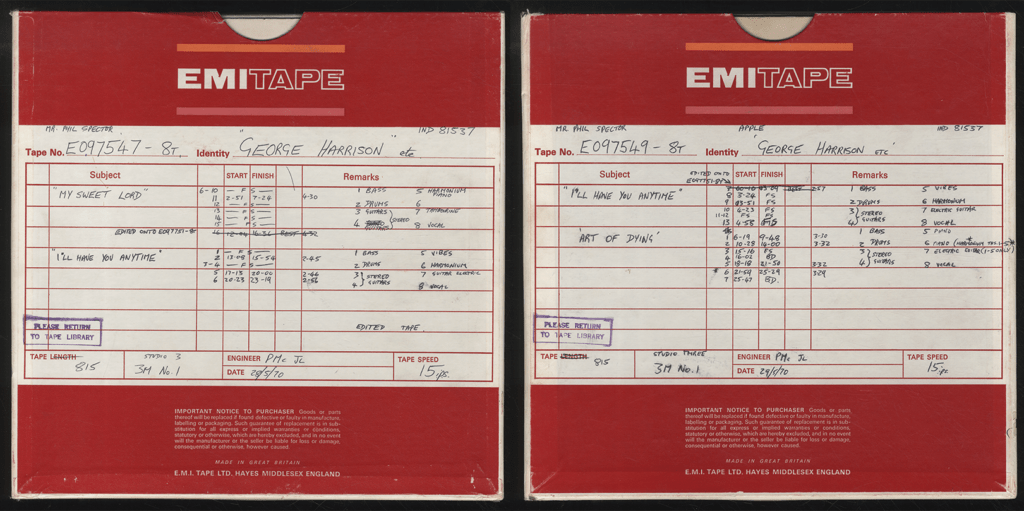

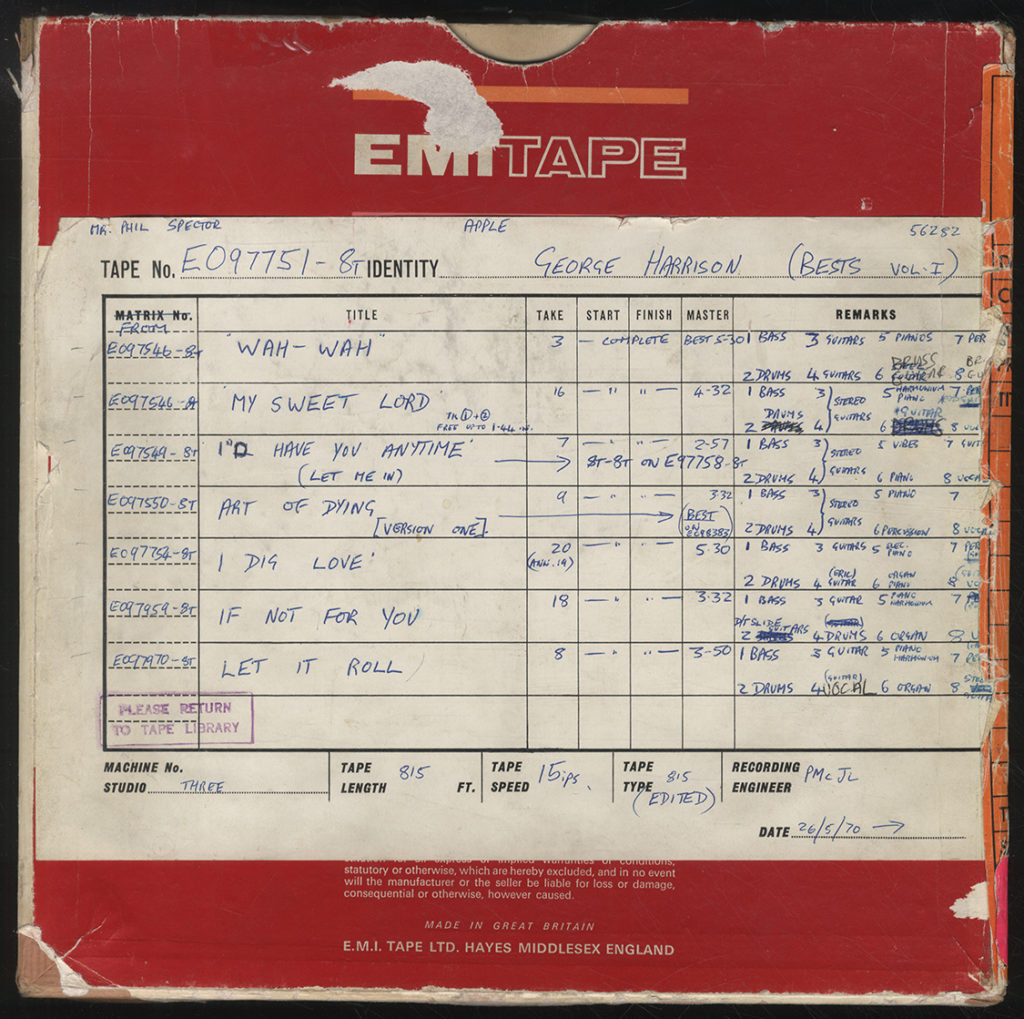

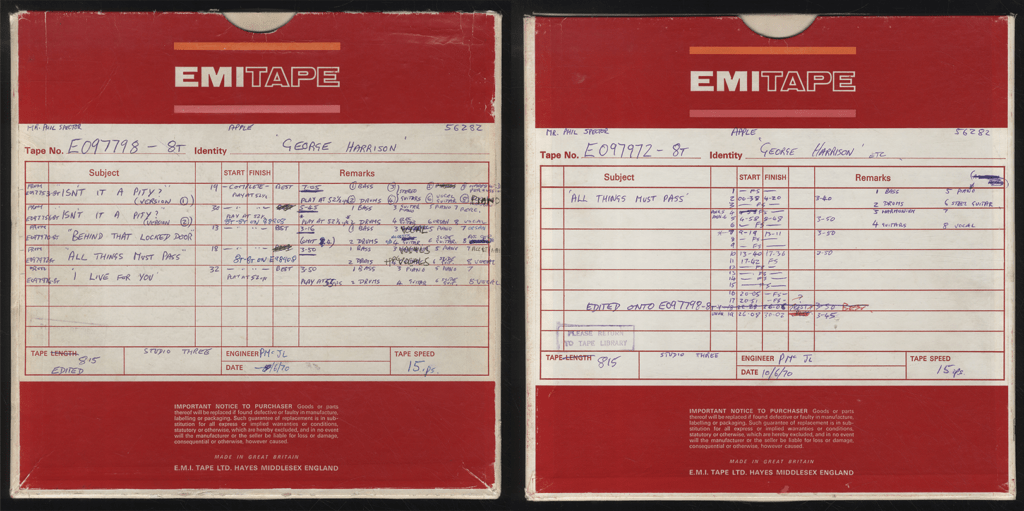

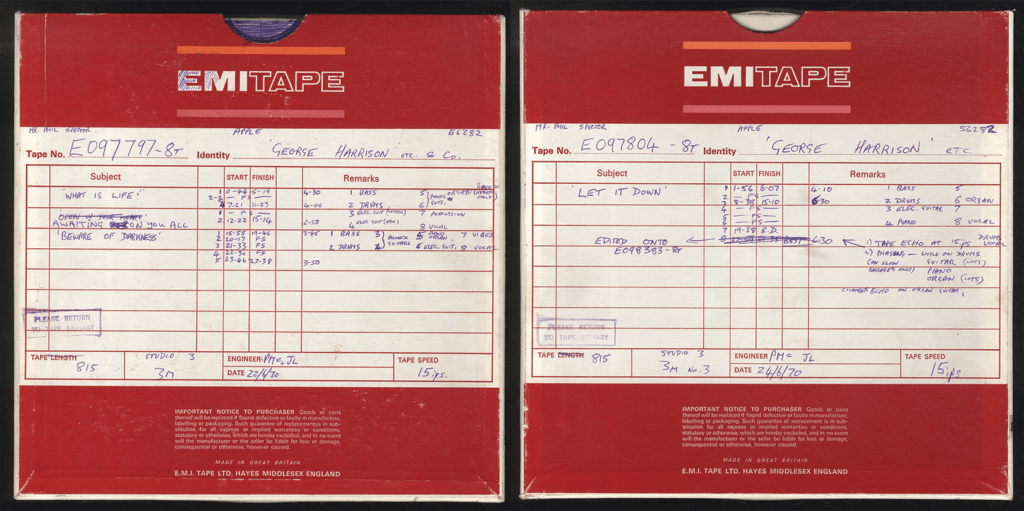

The mystery of who played on each track will will never be completely solved. The tape boxes from the sessions only indicate the instruments on each track, rarely naming the players. Some songs were recorded on more than one occasion, weeks apart with different sets of musicians, leading to contradictory accounts of the musicians on each song.

‘See, although the album was done on an eight- track tape, and there were some overdubs, most of those tracks had a lot of musicians in the studio and it was done as Phil Spector probably did his stuff back in the early 60s. That is to say it was routine that everybody knew when they came in – with the piano, the guitar solo, the tambourines – you just had to learn it and do it as a take. So most of those songs were done as a performance, really. And then with the vocal, you had to do it again, or we’d add the horns or strings, or whatever.’

George

Engineer Philip McDonald used the studio’s 3M M23 eight-track tape recorders and the TG12345 Mk I mixing desk throughout the session. McDonald had worked on sessions with The Beatles and had risen to become a top engineer at EMI Studios. This session would lead to Phil engineering and co-producing many of George’s solo albums.

‘I suppose I was a whizz kid at that time. I was an in-house engineer at EMI. I was supposed to do anything that came through the doors. I think George must have asked for me, but I can’t remember him asking me personally.’

Phil McDonald

The session got under way with a big line-up: Eric Clapton and his new American pals from Delaney & Bonnie’s band: Carl Radle, Bobby Whitlock and Jim Gordon, along with George’s A-team: Ringo Starr, Klaus Voormann and Billy Preston, plus Pete Ham, Tom Evans, Joey Molland, and Mike Gibbons from Apple Records’ band Badfinger playing acoustics and percussion. But Spector wanted more: multiple pianos, more acoustic guitars, more drums.

‘It was just Spector saying, “I think we need another piano,” so we’d call in a pianist, or “I need another guitarist” or “I need a percussion player”. But usually once they’d started learning a song then they’d do that one with the same people.’

Phil McDonald

Gary Wright from Spooky Tooth, Tony Ashton from The Remo Four, Peter Frampton and Jerry Shirley from Humble Pie, Alan White, who had played with The Plastic Ono Band at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival and on ‘Instant Karma’ and would later join Yes, Dave Mason of Traffic, Gary Brooker from Procol Harum, and Delaney & Bonnie / Joe Cocker / Rolling Stones’ horn section Bobby Keys and Jim Price were all called in the tracking sessions. Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees and a teenage Phil Collins spent at least one evening at Abbey Road playing on songs, though not on versions that were used on the album.

The arrangements for string and horns were written by one of George’s frequent collaborators, John Barham, and recorded at Abbey Road while George was doing overdubs in August, after the main tracking was completed. Abbey Road had been slow to install sixteen-track machines and George moved the sessions to Trident Studios in September to transfer some of the songs from eight-track to sixteen-track tape in order to create more open tracks for additional overdubs. The eight-track tapes were mixed at Abbey Road in early October and then the sixteen-track tapes were mixed at Trident, with the final mix completed on Saturday 17 October.

DEMOS

Tuesday 26 May – Wednesday 27 May

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

The first day of demos starts with two takes of All Things Must Pass.

‘When you go through all the stuff on Let It Be, there were occasions when we did All Things Must Pass, I tried that song. Well, not seriously, I just sang. It was probably me just trying to get somebody interested in one of my songs.’

George

George continues on the acoustic for Behind That Locked Door. George wordlessly sings his idea for the solo and says, ‘Go Pete’, referring to pedal steel guitar player Pete Drake, who will be flown in from Nashville two weeks later to play on several songs.

Up next is a single take of I Live For You, a song inspired by Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline that George planned on recording with Pete Drake.

This is followed by Apple Scruffs, which features George alone, playing guitar on track one and his vocal and harmonica on track two. Before the song George describes it as ‘skiffle rock’.

A second reel of eight-track tape is started and when Phil McDonald slates the next song with What Is Life Take 1, George quips, ‘Said the blind man to the shoe.’ ‘What Is Life’ – Take 3 is marked as BEST and overdubs were added to three more tracks on this take: a second vocal, a piano, and a guitar track by Voormann. It’s the only song on this day to have overdubs.

The songs were learned and recorded in quick succession. It only took one take of Awaiting On You All to show that the song’s arrangement, lyrics and George’s wonderful guitar intro and outro were pretty much complete.

‘He played the songs and then they learned it and then we did it. That’s how he worked all the time, George.’

Phil McDonald

Take 2 of Isn’t It A Pity features George’s guitar through a Leslie speaker, the amplified rotating speaker cabinets more commonly used with a Hammond organ, and used to great effect at the end of ‘Long, Long, Long’ on The Beatles.

I’d Have You Anytime features George alone on electric guitar and vocal, playing through the rotating cabinet again, changing the speed with the Leslie foot-pedal between verse and chorus.

I Dig Love starts the third reel of the day. This version has a very different feel to the album version, more upbeat, with George delivering a strong R&B-style vocal, and Ringo with a rocking performance.

Golders Green is an area of London where George would go to visit Apple Records’ band Badfinger, who had lived in a ‘band house’ there since 1966 when they were still The Iveys. There are three takes of the fun Carl Perkins/Elvis-styled Going Down To Golders Green with the second take marked ‘FS’. The engineers marked the takes that weren’t completed as either ‘FS’ for false start or ‘BD’ for breakdown.

Speaking about The Beatles’ 1968 trip to India in The Beatles Anthology, George said, ‘I wrote a number of songs that I’ve never recorded to this day. I wrote one called Dehra Dun.’ George records two takes, but ‘Dehra Dun’ doesn’t make it to the tracking phase with the full band.

George had spent the last week of January 1970 in the studio finishing the album The Radha Krsna Temple for Apple Records with a group of Hare Krishna devotees. Om Hare Om (Gopala Krishna) is very similar to the songs from that session. It is a devotional song based on Sanskrit mantras that George had learned in his studies of Indian devotional music. This song does move on to the tracking phase, but ultimately doesn’t make it to the album.

George’s demo of Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll) shows the lyrics still in progress and includes a backing vocal singing, ‘Oh, Sir Frankie Crisp’.

The only take of My Sweet Lord features Ringo with a laid-back drum track, a very different feel to the final version. George then goes back to ‘Apple Scruffs’ for another three takes, with only Take 4 being complete.

George ends the long and fruitful day with a revved-up version of Sour Milk Sea. A full day of singing lends a forceful growl to his voice as he delivers a strong performance closer to the version he produced for Jackie Lomax in 1968, than to his own ‘Sour Milk Sea’ Esher demo recorded prior to the sessions for The Beatles.

George has demoed fifteen songs in one day that are contenders for his solo showcase. Ten of these songs are destined for the final album.

Fifteen additional demos are recorded on the second day as George plays more songs from his deep reserves of unreleased compositions.

‘I was working on the record with Phil Spector. He was gonna co-produce with me so I had to sing him the tunes so he got an idea what the songs were about. The engineer just happened to stick a mic there and tape it. It was all done in a bit of a rush . . . “This one’s called this, this one’s called that,” just sang him a whole lot of songs, not all of which went onto the album. There was far more than was on this album.’

George

George performs all but one of the songs alone, playing either electric or acoustic guitar. Instead of using the multi-track tape deck, as on the day before, the songs were more hastily recorded on a two-track Studer A62 1/4” tape machine. Only one take of each song is recorded as George previews the songs for Spector.

George announces at the beginning of the tape, ‘It’s called Run Of The Mill, this one.’

The earliest versions of Art Of Dying in the George Harrison Archive can be found on a tape of demos alongside ‘Within You Without You’, as well as in the same pad of handwritten lyrics dating from late 1966 / early 1967, indicating that it is one of the oldest songs to make it onto the album.

‘Some of them I wrote about three years ago and I kept them hidden because I reckoned they were too far out. One was called “The Art Of Dying”.’

George

Continuing with the acoustic guitar, George plays Everybody/Nobody. He sings the refrain, ‘Oh, Sir Frankie Crisp’ once in the intro, more to acknowledge the chord structure shared with ‘Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp’ than to join the two songs. The only other version of ‘Everybody/ Nobody’ in the archive is on an undated personal cassette recorded by George during a visit with brother Pete & sister-in-law Pauline Harrison from late 1969.

Wah-Wah is the only demo on this day to have a bass part accompanying George on electric guitar.

Switching back to acoustic guitar, George records Window Window. This is another song that only appears here and on George’s personal cassette. It didn’t make it further than this demo, and there are no other extant versions in the George Harrison Archive.

Beautiful Girl is still untitled and unfinished when George presents it to Spector on acoustic guitar.

‘I started “Beautiful Girl” in 1969 – I’d been working on a Doris Troy record and Stephen Stills had a very good twelve-string guitar, which he loaned me for the evening. I wrote the tune then on that guitar but I couldn’t get past the first verse with the lyrics, and so the song sank back into the distance, but I remembered it during 1976 and finished the lyrics [for the Thirty-Three & 1/3 album]. I related it then to Olivia.’

George

A newer song, still a work in progress, is recorded next. Beware Of Darkness shows different lyrics to the final version and no fourth verse. With twenty-one other demos of fully written songs already recorded, it is a ‘dark horse’ to make it onto the album. (At this point there were no plans for a three-LP release. The remaining songs demoed on this day would have had little chance of making it onto a single LP release.)

Let It Down is played with just acoustic guitar, in stark contrast to the mammoth production of the final version on the album.

A second reel of tape is then started with George still on acoustic. He plays the only version of a song called Tell Me What Has Happened To You in the George Harrison Archive, or otherwise known.

George moves to electric guitar for the demo of Hear Me Lord, another unused song from the Let It Be sessions. It’s the last of the original songs demoed on this day that will make it to the final album, where it ultimately closes the second LP.

Nowhere To Go was a collaboration between George and Dylan from their 1968 Thanksgiving visit that also yielded ‘I’d Have You Anytime’. It was first called ‘Thingymubob’, then ‘When Everybody Comes to Town’. ‘I Get Tired’ was also a working title and finally, by the time of the All Things Must Pass sessions, it is titled ‘Nowhere To Go’.

George begins Cosmic Empire with an electric guitar, but then switches over to acoustic and restarts the song. At the beginning of the song he describes his vision of the arrangement as being, ‘full of chorus voices’ and with ‘hardly any voice other than just backing voices’. The song makes it no further than this demo, and does not otherwise appear in the George Harrison Archive.

Mother Divine is only recorded as a demo and is not recorded during the later tracking sessions or for any subsequent solo album, but Olivia has stated that George did play the song at home occasionally over the years, almost as a mantra.

The final two demos are songs that George has learned directly from Dylan and are still unreleased at that moment. George introduces I Don’t Want To Do It with ‘We’ll do this one tomorrow,’ but it isn’t tracked at all during the sessions. Dylan never released a version but George did finally record it fourteen years later and it was released in April of 1985 on the Porky’s Revenge! soundtrack.

The last of the thirty songs to be demoed is Dylan’s If Not For You, which does make it to the album. George had played slide guitar on a take of the song recorded on 1 May during Dylan’s New Morning album sessions at Studio B, Columbia Recording Studio in New York. Dylan will record another version of the song in August that is released in October, a month before All Things Must Pass, as the lead-off track on New Morning and the album’s only single.

Thirty songs have been demoed over the two days, and seven of the fifteen songs recorded on the second day will make it to the album. These seven songs and the ten selected from the previous day will become the two main albums of All Things Must Pass over the next six months.

TRACKING

Thursday 28 May – Friday 29 May

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

The tracking session formally starts with Wah-Wah – Take 1. Abbey Road’s 3M M23 eight-track tape machines are the same machines that had been used for The Beatles’ Let It Be and Abbey Road sessions. To capture the large band on only eight tracks certain choices have to be made. The drums are carefully sub-mixed from multiple microphones down to just one track. Multiple guitars and keyboards are also blended together onto single tracks, to help achieve Spector’s ‘Wall of Sound’.

‘In the control room it was different than the studio, a lot different. Spector had this echo on echo and there was this massive sound. And when George came in and he said, “Okay, play back,” Spector turned the volume up to very, very high – LOUD – and George just sat there, and I thought he was going to turn around and walk out but he didn’t. He said, “Interesting. Hmmm.” And we did like it in the end, but it was like his jaw dropped when he first heard the playback of what he’d just done.’

Phil McDonald

After only three takes they were happy with the results and marked Take 3 of ‘Wah-Wah’ as BEST. This section of tape is carefully edited out of its master reel and moved to start a new reel, ‘BESTS VOL. 1’.

Five takes of ‘My Sweet Lord’ – with only guitars, harmonium, and vocal – were attempted but all were incomplete. The instrumentation is changed back to the full band for the next reel, this time with harmonium and piano blended together on track five. The last one, Take 16, is marked BEST and edited to the compilation reel.

‘They had to learn the songs all together with Badfinger playing on “My Sweet Lord” with George, four acoustic guitars. I put this screen around the acoustic guitar because when you’ve got an acoustic guitar the mic is fairly live so you want a bit of protection, so I put this half soundproof box around George.’

Phil McDonald

The piano is replaced by vibes for George’s co-write with Dylan that ultimately opens the album. I’d Have You Anytime – Take 5 is one of the six takes that are recorded before they call it a day. Eric Clapton plays the lead guitar on the song’s intro.

‘He’s on nearly every track there is, like the very first note on the album is Eric on “I’d Have You Any Time”.’

George

Friday starts with Take 7 of ‘I’d Have You Anytime’, which is deemed the BEST take and edited to the compiled reel.

George is heard asking Ringo to come in on Art Of Dying – Take 1 with a snare hit on the upbeat before the song starts. George calls out some of the changes in the song as he’s singing, and in the third verse he sings, ‘desire to be / A perfect cup of tea’ instead of ‘desire to be / A perfect entity’. After Take 5 the harmonium track is replaced with the second piano, resulting in two separate piano tracks rather than blending them down to one track as usual. One more complete take is made before they switch reels. At this point the two pianos are mixed to one track and a percussion track is set up. After one false start they record ‘Art Of Dying’ – Take 9, which is deemed the BEST and edited to the compiled reel, but ultimately the song is re-recorded in both June and July and this version does not make it to the album.

Two takes of ‘Run Of The Mill’ are performed on this day, with George alone, on guitar and vocal. They marked Take 2 as BEST and initially indicated it would be moved to the reel of BEST takes, but in the end it is returned to this reel.

All eight tracks of the M23 tape machine were in use for their initial try at ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ – bass and drums on tracks one and two, multiple guitars blended to a ‘stereo’ guitar track on channels three and four, two pianos on track five, Moog synthesizer on channel six, electric harpsichord and percussion blended together to track seven, and George’s vocal on track eight. The full ‘Wall of Sound’.

‘We only had eight tracks so you couldn’t go mad. You were just restricted. You had to get the sound and mix it and make sure it was a good sound.’

Phil McDonald

They aren’t satisfied with ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ or ‘Art Of Dying’ and will return to both, but after a solid two days of work with the band they have the basic tracks for three songs: ‘Wah-Wah’, ‘My Sweet Lord’ and ‘I’d Have You Anytime’.

Tuesday 2 June – Friday 5 June

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

The sessions continued after three days off with the addition of more musicians.

‘It was just Spector saying, “Give me that” and “Get me more of that,” and of course George did it. He got people and then he said, “Do you think we need some more of this?” Whatever he wanted, he got, Spector, really. He’d say, “I think we need another piano,” so we’d call in a pianist, or “I need another guitarist,” or “I need a percussion player.” I don’t know really how he did it, but he just got this sound in the end and sometimes you’d hear the overtones. He’d write a choir line or pick out a tune in all the overtones. He was very clever.’

Phil McDonald

Spector wanted additional keyboards for the next attempt at ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ and Voormann called someone that he had worked with: Gary Wright, the keyboardist from Spooky Tooth. Gary was in a session at Olympic Studios, but dropped everything and came straight over to Abbey Road, where he met George for the first time:

‘The group had been rehearsing “Isn’t It A Pity” when I arrived. George took his acoustic guitar and began showing me the chord changes, which I nervously wrote out on a chord chart.’

Gary Wright

The second attempt at the song goes slowly and George’s frustration with the increasing number of takes is evident, as he sings, ‘Isn’t it so shitty? Isn’t it a pain? How we do so many takes. Now we’re doing it again’ on Isn’t It A Pity – Take 14, which opens Disc 5. Take 19, the final take, does eventually make it to the album as ‘Isn’t

It A Pity (version one)’, but is not yet considered the definitive version. On the box they note that it is the ‘1st Version’. It is later moved to the second compiled reel of BEST takes for additional overdubs.

Thirty-one takes of ‘I Dig Love’ are recorded on this day, with ten shown as completed takes. Take 20 is chosen as the BEST take and edited to the compiled reel. The engineers’ track information on the tape boxes rarely indicates the musicians by name, but in this instance did note ‘ELEC. GUITAR (ERIC)’ on track five.

They call it a day with one BEST take of ‘I Dig Love’, and a preferred take of ‘Isn’t It A Pity’, but plan to try a different arrangement the following day.

On Wednesday 3 June, not completely satisfied with the results of ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ from the day before, they change the arrangement – with organ, piano and a lead guitar all featured in the intro – and the tempo is slightly slowed. Isn’t It A Pity – Take 27 presents the listener with the simple but exquisite instrumentation and arrangement of the basic track.

‘Isn’t It A Pity’ – Take 30 is picked as the BEST. It had taken a full day, but they had the take that would become ‘Isn’t It A Pity (version two)’ on the album.

The next day, Thursday 4 June, they start a new song and add another musician. George has invited Peter Frampton to the All Things Must Pass sessions to expand the acoustic guitar section. George had met Frampton during the Doris Troy sessions, when he lent Frampton his famous Les Paul guitar, ‘Lucy’, to play on ‘Ain’t That Peculiar’.

‘He asked me would I come and play. That’s when I went in, and it was me, and then George to my right, and then to his right were the three Badfinger members.’

Peter Frampton

The first two attempts at ‘Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)’ were not complete. Take 1 breaks down after about 1 min 30 secs with George saying, ‘Yeah, that felt really nice, Gary, that going up, you know, like building up and up.’ George jokes over the start of Take 2 that ‘Earl Scruggs on banjo would do that good,’

and emulates a banjo part, ‘rinka-dinka rinka- dink.’ Although George comments, ‘That felt nice,’ they move on to the next song.

Up next is Dylan’s ‘If Not For You’. During Take 1, George explains the arrangement of the song to the band: ‘It’s intro for a bit then two verses. After two verses there’s two of those [plays guitar chords], then it goes to C.’ If Not For You – Take 2 is recorded with acoustic guitars, organ, piano, bass, drums and vocal. The tempo is faster than the final version and the drums are played with sticks, whereas they will switch to brushes for the take that makes it to the album.

Friday starts off with more takes of ‘If Not For You’. After the first attempt of the day, Take 9, George comments, ‘It seems it’s all gone. Not as good to me now. I preferred it with the brushes.’ Then before the final take he says, ‘Hang on. There’s too many fiddlin’ on the guitars. I think it should all just be straight.’ The next and final take, ‘If Not For You’

– Take 18, is deemed the BEST and edited to the compiled reel.

They return to ‘Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)’ for several attempts, ending with one complete take, ‘Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)’ – Take 8, which is moved to the now full reel of ‘BESTS VOL 1’.

‘Behind That Locked Door’ is next, with George playing slide for the first time in the session, a part soon to be doubled by Pete Drake’s pedal steel guitar. The thirteen takes include four complete takes, and the final one, ‘Behind That Locked Door’ – Take 13, is chosen as the BEST.

The basic tracks for three songs have been completed, the most songs in one day. They now had ‘basics’ complete for ten songs after six days of tracking, ready for overdubs of more instruments and vocals. A second compilation reel is started with the BEST choices of the two ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ versions and ‘Behind That Locked Door’ – Take 13.

Badfinger’s work on All Things Must Pass ends as they leave for a Capitol Records Convention show in Honolulu, Hawaii, followed by a festival in Germany and a tour of the UK.

Tuesday 9 June – Friday 12 June

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio

Three Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

The band returns to the studio with the notable addition of Pete Drake, the Nashville pedal steel guitar player.

‘George was making the album and I sent my car for this steel guitarist and producer Pete Drake, from Nashville. So Pete came and he noticed in my car I had all these country tapes. I don’t know why he was shocked at this but he goes, “Wow, you’ve got all these country tapes!” “Yeah. I love country music.” He said, “Well, why don’t you come to Nashville and we’ll make a record?” So I flew to Nashville because of him and we did Beaucoups Of Blues.’

Ringo Starr

The first song recorded is ‘I Live For You’. After one false start, George chats to Ringo suggesting a different, ‘tikka tikka’ rhythm. The band then settles into a couple of takes at a faster tempo than the final version, which George describes as ‘something that rolls along more, rather than being sort of strict rock beat’.

After Take 3 there is an impromptu jam of the old barbershop standard Wedding Bells (Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine) – Take 1, which had been covered by Gene Vincent on his 1956 Bluejean Bop album. It is just weeks after The Beatles’ breakup and the release of the Let It Be album and film, so the lyrics take on an added layer of poignancy.

They revisit ‘I Live For You’ in a more mellow vibe on Takes 5 and 8 with some false starts in between and another impromptu bluesy jam after Take 10, prompting George to tell the band, ‘Let’s just try and get it now ’cos it’s really silly!’ Takes 11 and 12 are only partial, but have Ringo playing a shaker instead of hi-hat and the band returning to a faster, more upbeat feel with Takes 13 and

15 being complete, as they try to find the groove. They end with the complete Take 16, which feels closer to the final full-band version including electric guitar with vibrato effect.

The following day, with Pete Drake still in attendance, they record what would become the title track of the album, ‘All Things Must Pass’. George seems dissatisfied with the feel and between Takes 5 and 6 asks, ‘What’s the timing? It tends to be, like, a bit not relaxed enough. Seems to be going slow and fast, not just easy.’ Take 18 is marked BEST and edited to the compilation reel.

George can be heard throughout the sessions working out the arrangements and tempos with the band in the studio while Spector, in the control room, ponders the layers of instruments that he wants to hear on each song to achieve the combined sound that comes from the orchestra of instruments. The dynamic between George and Spector as co-producers is fairly balanced. It’s clear from the tapes and interviews with those at the session that George is actively involved in the production on the album.

‘George was pretty matter-of-fact and they would talk together and it was pretty much equal. George knew exactly what he wanted. That was the great thing. After every take, we all did go into the control room because that’s what bands do but Phil Spector never, apparently, allowed any musician, session musician, or artist to even come in the control room and whenever we did come in, he looked very uncomfortable.’

Peter Frampton

The band then returns to ‘I Live For You’ with the same instrumentation/tracking as the previous day. They start off slowly, with George commenting that, ‘We just go, after the second bridge and there’s the last verse (hums arrangement) but it’s slightly slow, you just feel that.’ They gradually increase tempo until by Take 26 they arrive at a feel very similar to the final version, Take 32, which is marked as BEST? and moved to the second compiled reel. ‘I Live For You’ didn’t make it onto the original album release, but did officially see the light of day with the 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass, when George re-recorded the song, keeping only the lead vocal and Pete Drake’s pedal steel guitar from this take.

‘Coming back to it, I fixed the drums up very simply. But the main thing about it for me is the Pete Drake solo on pedal steel guitar. He died [in 1988], and I often thought if his family is still around, then suddenly they’ll be hearing him playing this thing that they’ve never heard before. I really loved his pedal steel guitar – the bagpipes of country & western music.’

George

Then a return to ‘Art Of Dying’, which they had recorded nine takes of on 29 May. One version is recorded, Take 10, a more pared back, acoustic version of the song with drums played with brushes, bass, acoustic guitars, harmonium, piano vocals and congas.

Pete Drake is still in the studio for Thursday and Friday, but no additional songs with the full band are recorded. Instead, over these two days Pete overdubs pedal steel onto the BEST takes

of two songs that were tracked before he arrived, ‘Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)’ and ‘Behind That Locked Door’.

George records three takes of ‘Woman Don’t You Cry For Me’, the last take with mouth harp and foot taps. George wrote the song while on tour with Delaney & Bonnie the previous year. It’s recorded direct to two-track tape, apparently more of a demo or reference than an attempt to record the song for the album. George will return to it on 7 October when he goes into the studio to record ‘It’s Johnny’s Birthday’.

Friday 12 June is the final day with Pete Drake and he demonstrates his ‘talking steel guitar’ – a ‘talk box’ that he used with his pedal steel guitar for his 1964 country music hit ‘Forever’. He plays some of ‘Danny Boy’ and ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ to demonstrate the effect. This is when Peter Frampton learns about the ‘talk box’ that he will soon acquire and use on some of his biggest hits.

‘He put this tube in his mouth and started playing the pedal steel and, oh my God, it was unbelievable. And we were just going wild about it and I said, “Where do I get one of those?” He said, “Well, I made this one myself,” and then after that he lent that exact talk box to Joe Walsh to do “Rocky Mountain Way”. Then Joe went to Bob Heil of Heil Sound and said, “Hey Bob, make me one that’s louder.” So, that’s where the Heil talk box comes from and Bob Heil gave me one for Christmas because he knew I loved it and the rest is history.’

Peter Frampton

No additional new songs are tracked on this day and they begin a ten-day break during which Derek & The Dominos will play their first show as a band and record their first single.

Thursday 18 June

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

Derek & The Dominos make their debut public performance at the Lyceum Theatre in London on 14 June. Dave Mason, guitarist from Traffic, joins the band onstage in a role that will soon be filled by Duane Allman when the band decamps to Miami.

As a return favour for playing on the All Things Must Pass sessions, George and Spector join Derek & The Dominos on 18 June for their first recording session and record ‘Tell The Truth’ and ‘Roll It Over’ with Spector producing, and George and Dave Mason both playing guitar. It’s been said that these sessions are at Apple Studios, but Phil McDonald remembers them taking place in Studio Three at Abbey Road.

As well as the two songs that will become the first Derek & The Dominos single, the band records jams that are later edited to become ‘Thanks For The Pepperoni’ and ‘Plug Me In’ on the bonus ‘Apple Jam’ LP in the original release of All Things Must Pass.

Monday 22 June – Wednesday 24 June

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

After a break of over a week, the session resumes on Monday 22 June with three more songs that have not yet been attempted by the band. What Is Life – Take 1 is a complete run-through at 4 minutes 30 seconds, with a shorter guitar solo, bouncy bass line and straighter drum feel compared to the album version. Notably the distinctive fuzz guitar riff from the album version was not present at this point.

They then turn to ‘Awaiting On You All’ – originally listed as ‘Open Up Your Heart’ – for a couple of takes. The first is incomplete but the second is a full take, again with a straighter feel than the final album version and George laughing his way through some of the vocals.

George tells the band before ‘Beware Of Darkness’ – Take 1, ‘The organ’s playing on this one. We’ll have rhythm guitars and organ right from the top.’ They end the day with five takes of the song.

‘That was a great track to cut, we had two drummers and two bass players, Klaus played a six-string bass and Carl played a four-string bass, Eric, me and Dave Mason all played guitars.’

George

They have learned three new songs and return to two of them on the following day.

On Tuesday 23 June they continue work on ‘What Is Life’ with Take 12. A definitive take of the song is still proving elusive and they fill a tape with takes without finding the right feel. The band does one more, slower version, Take 27, before the session continues with Takes 6 to 14 of ‘Beware Of Darkness’. Track seven is marked as ‘Elec. Guitar George’, Clapton’s electric guitar is on track five, vibes and guitars on track three, and organ on track four. Take 6 is marked as BEST and edited to the compilation reel. Beware Of Darkness – Take 8 features Clapton playing guitar through the Leslie speaker.

The last song of the day is ‘Hear Me Lord’. The song was written and auditioned to little response during the Let It Be sessions. George can be heard on 6 January 1969 at the Twickenham set saying that he had written it over the weekend. Now, a year and a half later, George has a band eager to learn and record the song. Before Take 1, George says, ‘Shall we try it, then, we all come in together at the top?’ The first take breaks down, so they discuss the arrangement before recording two more takes.

Wednesday 24 June starts with ‘Hear Me Lord’ – Take 4 which breaks down, but Hear Me Lord – Take 5 is a longer version than on the album, with an extended solo by Eric as they all jam on the outro. Take 8 is marked as BEST and is edited to the compiled reel.

Moving on, they turn to ‘Let It Down’ and perform eight takes, of which Let it Down – Take 1, 3 and 8 are complete with 8 marked as BEST. At the top of the take George describes the arrangement, singing and playing parts on his guitar to illustrate his points. The instrumentation is much less complex than most of the songs – just bass, drums, electric guitar, one piano and one organ.

Next up is an early run-through of ‘Om Hare Om (Gopala Krishna)’ of which Takes 1 and 3 are complete. They return to ‘Run Of The Mill’, first attempted in a different key on 29 May. The first two takes were performed by George on his own with just acoustic guitar; now, however, there is a full band backing him. This appears to be just a rough run-through, and both takes are incomplete.

Friday 26 June

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Two

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

Friday’s session is, for the first time, in Studio Two of Abbey Road instead of Studio Three. They start at 2.30pm and spend the entire afternoon and evening on ‘Awaiting On You All’, which was first attempted on 22 June. There are multiple changes of instrumentation until they arrive at the final Take 25 where percussion is noted on track 3, brass on track 7, and Clapton on slide guitar on track 8. ‘Awaiting On You All’ – Take 25 is marked BEST.

Ringo is not present at the session because he has flown to Nashville to record a country album with Pete Drake producing. In only three days they record fifteen original songs for what will become his second solo album, Beaucoups Of Blues.

Tuesday 30 June – Friday 3 July

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

‘Run Of The Mill’ is the focus as the band returns to Studio Three after the weekend. Run Of The Mill – Take 36 is faster than the album version with a distinctive dual-guitar part that is probably played by Clapton and Dave Mason. The Derek & The Dominos sound is developing at a rapid pace in the middle of the All Things Must Pass sessions, all the more so now with the departures of Ringo and Badfinger.

After Take 39 there’s another light-hearted moment as the band starts playing a jam, listed on the tape box as Down To The River (Rocking Chair Jam) – Take 1. Featuring George on lead yodel, with jazzy trumpets, harmonium and a walking bass line, it’s based on ‘Waitin’ For A Train’ by Jimmie Rogers, ‘The Singing Brakeman’, and his unique style in general. George’s father, Harold, was a fan of Jimmie Rogers and had several of his records in his collection. George would revisit the song, albeit in slightly mellower vain with modified lyrics and without the yodelling, on Brainwashed as ‘Rocking Chair In Hawaii’.

‘George did a country and western version when he was recording All Things Must Pass. He didn’t have all the words to it and he was sort of yodelling around in the background. I was really surprised because I thought “Rocking Chair In Hawaii” was written since living in Hawaii but it actually had been around in some form since way back when.’

Olivia Harrison

As the sessions move into July on Wednesday, George and the band carry on with ‘Run Of The Mill’. From Take 40 onwards there is a new arrangement, with a switch to the familiar stereo acoustic guitars of the final album version instead of the stereo electric guitars used up to this point. They are still working the arrangement out, with Eric heard at one point asking, ‘Hey Jim and Bobby, what is that lick you’re playing at the end, can you play me the harmonies you’re playing?’ George also says, ‘Can we stay on that A chord for, like we were doing last night? Twice as long,’ and plays his guitar to illustrate what he means. He also checks the tempo several times, saying, ‘And we’ll try and not slow down.’

The band catches the engineers by surprise with a jam of The Beatles’ Get Back – Take 1, released as a single only the previous year, after which George announces, ‘OK, everyone has toast!’ They then return to ‘Run Of The Mill’, with Take 45. George asks someone to ‘knock a few lights out and make it like home’. There are several complete takes which have a laid-back feel, but gradually move closer to the feel of the final album version by Take 53. The final take, ‘Run Of The Mill’ – Take 61 is marked as BEST.

They move on to ‘Art Of Dying’, carrying on from Take 10 on 23 June. The notes written on the boxes reveal some interesting details: Take 14 sees a change with the stereo guitars on tracks 3 and 4 replaced by Eric’s guitar on track 3 and ‘two guitars’ on track 4, and it is noted that there is no brass on these takes. From Take 17 onwards there is ‘cloth on snare’. From Take 26 onwards there is brass on track 7. ‘Art Of Dying’ – Take 26 is marked as BEST.

The only recording from Thursday 2 July is a twenty-minute jam later edited down to become ‘Out Of The Blue’ for the bonus ‘Apple Jam’ LP in the original triple-album box. Because the musicians were credited for this improvisation we can tell that they include George, Eric Clapton, Jim Gordon, Carl Radle, Bobby Whitlock, Gary Wright, Jim Price and Bobby Keyes. Journalist Al Aronowitz is also among the credits. Aronowitz was a colourful character who first introduced The Beatles to Dylan in 1964. He is more of a participant than a player and when asked what instrument he had played on the song he would reply with a shrug, ‘Typewriter?’

‘For the jams, I didn’t want to just throw ’em in the cupboard, and yet at the same time it wasn’t part of the record; that’s why I put it on a separate label to go in the package as a kind of bonus . . . We used to do that ourselves you know, the Fabs, back in the early days. So you’d have a break, somebody’d go to the toilet, they have a cigarette, and next minute you’d break into a jam session, and the engineer taped it on a two-track. When we were mixing the album and getting toward the end of it, I listened to that stuff, and I thought, “It’s got some fire in it,” particularly Eric. He plays some hot stuff on there!’

George

On Friday 3 July the band returns to ‘What Is Life’, last attempted on 23 June, with Takes 28 to 42. This has Eric on guitar on track 3 and George playing ‘fuzz guitar’ on track 4. ‘What Is Life’ – Take 42 is marked BEST.

A succession of jams are found between takes of ‘What Is Life’ including ‘Jam (4)’ which is then titled Almost 12 Bar Honky Tonk by George in his production notes. This will be the final day in the studio with a full band.

George leaves at this point to see his ailing mother. Louise Harrison passes away on 7 July.

With George’s sudden departure, the Dominos find themselves at another session, backing Dr. John

at Trident for his album The Sun, Moon & Herbs. In August they embark on a UK tour and then fly to Miami by the end of the month to record their album at Criteria Studios with Duane Allman added to the line-up.

Saturday 25 July

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three Engineers: Philip McDonald, ‘JB’

George returns to the studio to start the process of adding overdubs to the BEST choices on the compiled reels, but first he records ‘Apple Scruffs’ – written for the fans who are to be found patiently waiting outside the studio every day. With the band gone, George records with just acoustic guitar and harmonica.

‘I was sitting on a stool that had a metal foot bar on it and so the engineer put a microphone on that, so that’s like the click track is just this banging on that and I had the harmonica track and so that was all done live.’

George

From Take 16 onwards a microphone is set up to record Mal Evans tapping his foot, instead of George doing it while playing and singing. They pick Take 18 as the BEST. George decides to play the new track for the ‘scruffs’ who happen to be outside.

The basic tracking for the All Things Must Pass album is complete with the exception of ‘It’s Johnny’s Birthday’, which is recorded in October.

‘We just said, “We’d better check out where we are,” and we had eighteen tracks. And so we thought, “better just finish them off now,” because the account- ant kept coming down and saying “Are you gonna be much longer here? It’s already cost us forty quid!”’ George

OVERDUBS

Monday 27 July – Monday 12 August

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three, Studio Two

Engineers: Philip McDonald, Richard Lush, John Leckie

George spends the first half of August working on the songs in Studio Three at Abbey Road with engineers Phil McDonald and Richard Lush. Spector is present for some but not all of these sessions. George does most of his slide work on the album during overdubs.

‘He created a sound on the slide that I don’t think I’ve heard anybody else have. It was instant recognition. As soon as you heard that sound you knew. He overdubbed the intro on “My Sweet Lord”. He overdubbed a lot of slide because he didn’t play it live during the tracking.’

Phil McDonald

In order to create enough room to add more instruments and vocals, on Monday 27 July they start the process of transferring the eight-track BEST choices to another eight-track machine, blending tracks together to create more open tracks. Derek & The Dominos and Badfinger are now both off on tour so George brings in Gary Wright or Peter Frampton when help is needed with additional overdubs.

‘About two weeks later, after that week of sessions that I did [on the basic tracking], George called up and said, “Hey Peter, Phil wants more acoustics.” So I said, “You’re kidding me?” He said, “Bring your acoustic.” So, we’re sitting on two stools in front of the glass and there’s Phil sitting in there. George and I are overdubbing first on the tracks that I played on with him and Badfinger and then Phil says, “Well, this is going great. Let’s do more.” George would just shout out the chords right before each take, and off we went.’

Peter Frampton

George works directly with classical pianist and arranger John Barham on creating and recording the orchestral arrangements. Barham became a student of Ravi Shankar in 1966 and worked with George extensively during the making of Wonderwall Music. More recently, Barham has provided the orchestral arrangements for Spector’s production of the Let It Be album. Brass and strings are added towards the end of the overdub session, after Spector’s somewhat hasty departure to the United States upon realising he has overstayed his visa.

‘I did all the preparation at Friar Park just shortly after they moved in. And George was working

on an upright piano. And anything George wanted, like a riff or anything like that, he’d just either play it or sing it, and I’d just notate it immediately. I didn’t create any riffs. If there’s anything that stands out as a riff, it’s because George wanted it there.’

John Barham

Thursday 2 September – Saturday 12 September

Studio: Trident

Engineers: Ken Scott, Dave C.

Abbey Road has been slow to put sixteen-track tape recorders into service but other studios in London are already using them. George moves to Trident Studios in September to transfer the eight-track tapes to sixteen-track, giving him eight new empty tracks to work with. Spector remains in the US and isn’t present for this new round of overdubs.

‘I took ten or eleven of the tracks to try in the studio off Wardour Street, put them onto sixteen-track,

’cos at that time Abbey Road only had eight tracks. And of those tracks, then we overdubbed the ones that turned into the most noisy tracks on the album like, “What Is Life”, “Let It Down” and “Awaiting On You All”, “Wah-Wah”, all those ones that have big noise. So those tracks were done in Trident, mixed in Trident and the others remained as just eight tracks.’

George

Engineer Ken Scott has been a familiar face at Abbey Road since 1964, working on many sessions for The Beatles. In late 1969 he moved over to Trident. George has already worked there on several projects. The Beatles recorded ‘Hey Jude’ there in 1968 when Trident had an early eight-track machine and Abbey Road was still using four-track machines. The Beatles also recorded several songs from The Beatles at Trident including George’s ‘Savoy Truffle’.

George uses the extra tracks to add layers of his own backing vocals, noted as the ‘George Harrison

Singers’ in his production notes before becoming the ‘George O’Hara-Smith Singers’ in the credits.

‘George knew what he wanted to do. It was all these massive backing vocals, which were, in the most part, just him. And it was putting down a whole bunch of parts, bouncing them to a track, putting down a whole bunch of others, and just piecing together all of this amazing music.’

Ken Scott

George also adds more piano, tambourine and other percussion to the newly available open tracks. Rough mixes are made on Saturday 12 September to wrap up the overdub sessions.

MIXING

Tuesday 6 October – Friday 9 October

Studio: Abbey Road, Studio Three, Room 4

Engineers: Philip McDonald, John Leckie

The songs on eight-track tapes that have not been taken over to Trident for the sixteen-track treatment are mixed at Abbey Road, beginning in early October. Spector has returned to London and is also working with John Lennon down the hall at Abbey Road for what will become the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album.

On 7 October while mixing ‘I’d Have You Anytime’, ‘Run Of The Mill’, and ‘I Dig Love’ in Room 4, George finds time to go into into Studio Three to record It’s Johnny’s Birthday – Take 1 with some backing vocals from Mal Evans and engineer Eddie Klein.

George also records the final song of the session, Woman Don’t You Cry For Me – Take 5, the first song that he has written to feature slide guitar, composed while on tour with Delaney & Bonnie the previous year.

Saturday 10 October – Saturday 17 October

Studio: Trident

Engineers: Ken Scott, Dave C.

To mix the sixteen-track tapes George returns to Trident, this time with Spector.

‘George and I would start right about 2.30, 3 o’clock every day. We take it to a certain point where we got comfortable with the mixing. And then Spector would come in and say, “Try a bit more of this, a bit more of that on there.” And okay that’s it, and he’d go, and we’d finish it off. And George would go and we’d set up for the next day, the next title we’re going to do and it would be the same thing. Come in around 2.30, 3 o’clock, get the mix to where we were comfortable. Spector would come in, “Change this, change that,” then, “Okay” and then go, and we’d finish it off.’

Ken Scott

The album is then mastered at Trident with separate sets of tapes made for manufacturing in different markets. George carries over a set for the US pressing when he travels to New York on 28 October.

‘My Sweet Lord’ b/w ‘Isn’t It A Pity’ is released in the US on 23 November. Six months after starting at Abbey Road. All Things Must Pass is released on 27 November 1970.

Archival Notes by Don Fleming and Richard Radford

The session information is based on the original All Things Must Pass production notes,

photographs and reel-to-reel session tapes in the George Harrison Archive.

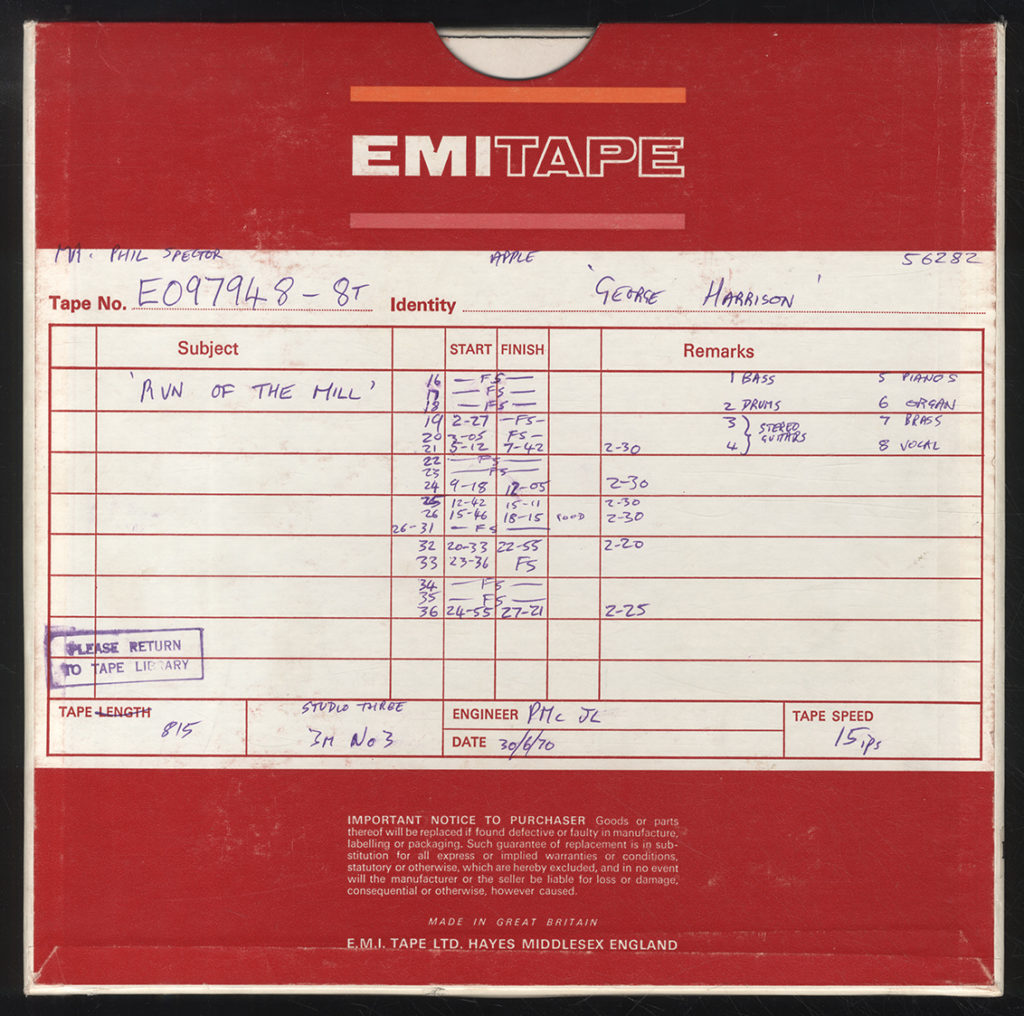

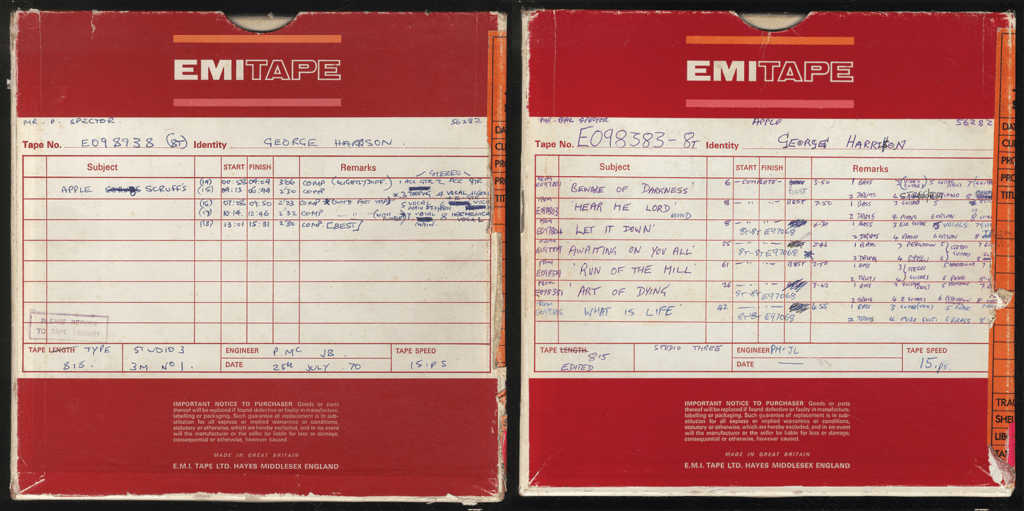

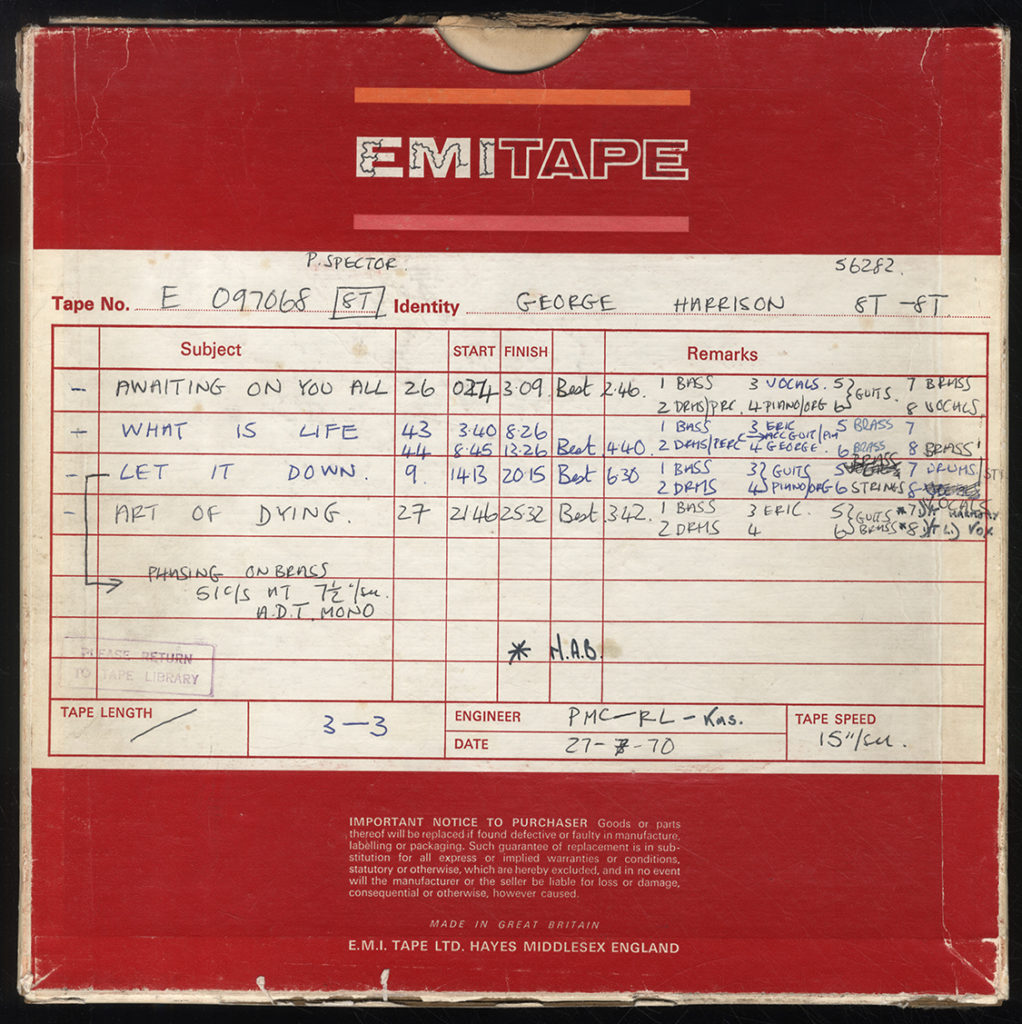

The All Thing Must Pass session tapes created in 1970 include forty-nine 1” eight-track tapes, four 2” sixteen-track tapes, and forty-four 1/4” stereo tapes. Over twenty-five hours of music is documented. The chronology of the making of All Things Must Pass is derived from

the engineer’s information on the tape boxes.

Richard Radford, Archivist for the George Harrison Archive since 2006, oversaw the latest

preservation of the tape collection. The multi-track and stereo tapes were transferred

to 192 KHz/24bit digital preservation copies from the original analogue tapes

by Matthew Cocker, Richard Barrie, and Paul Hicks.